James Stinson, York University, Canada and Lee Mcloughlin, Florida International University

Driven by extreme heat and drought, some of the worst wildfires in living memory raged across Mexico and Central America through April and May 2024.

News agencies reported howler monkeys dropping dead from trees, and parrots and other birds falling from the skies.

In Belize, a state of emergency was declared as wildfires burned tens of thousands of hectares of highly bio-diverse forest. Farmers suffered huge losses as fires destroyed crops and homes, and communities across the country suffered from hazardous air quality and hot, sleepless nights. Many risked their lives to fight off the approaching fires.

As the wildfire crisis subsided with rains in June, public attention shifted toward identifying the causes and allocating blame. Many singled out the “slash and burn” farming practices in Belize’s Indigenous communities as the primary cause. This simple knee-jerk reaction ignores the underlying causes of the climate crisis, are scientifically unfounded and stoke resentment of Indigenous Peoples.

Fanning the flames

On June 5, one of Belize’s major news networks ran a story with the headline “Are Primitive Farming Techniques Responsible for Wildfires?” The story placed blame for Belize’s wildfires on “slash-and-burn farming”, arguing that “there has to be a shift away from this destructive means of agriculture.”

The story was followed by an op-ed published online asserting that “because of the increased amounts of escaped agricultural fires, aided by climate change, global warming and drought, slash and burn has become more of a problem than the solution it once was.” This sentiment was further reinforced by Belize’s prime minister, who declared that “slash аnd burn has to be something of the past.”

While some of the recent fires in Belize were connected to agricultural burning — and poorly managed fire-clearing practices can have negative air-quality impacts — blaming “slash and burn” for the wildfire crisis ignores the larger context and conditions that made it possible, namely global warming.

May 2024 was the hottest and driest month in Belize’s history. This extreme heat is part of a broader global trend, with June 2024 marking the 13th consecutive “hottest month on record” globally.

More fundamentally, these statements confuse other forms of slash-and-burn agriculture with the distinct “milpa” systems employed by Indigenous people in Belize.

Indigenous knowledge undermined

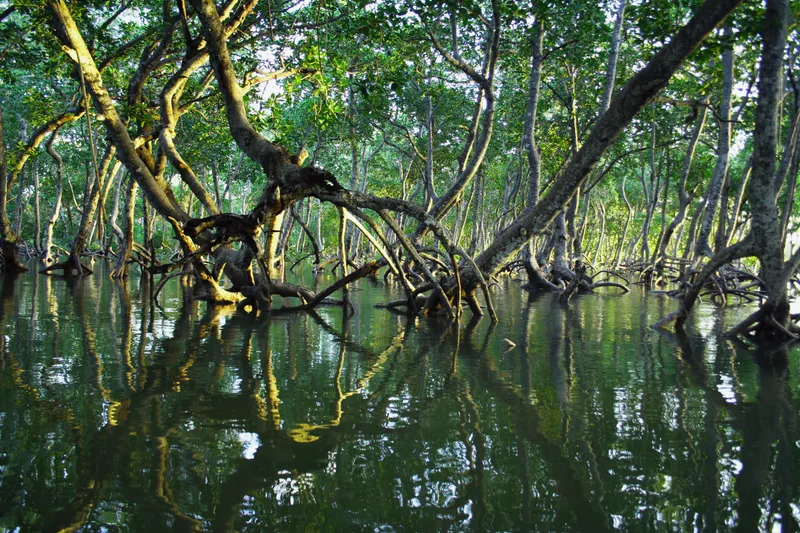

Throughout Belize, Indigenous Maya farmers commonly practise a form of agriculture referred to as milpa in which fire is used to clear fields and fertilize the soil. Within this system, small areas of forest are chopped down, burned, and planted with maize, beans, squash and other crops. After being cultivated for a year or two, the field is then left fallow and allowed to regenerate back to forest cover while the farmers move on to a new area within a cyclical pattern where areas are reused after a regenerative period.

Commonly derided as slash-and-burn farming, milpa has long been perceived as environmentally destructive. This perspective has been perpetuated by long-standing myths and misconceptions that portray the farming practices of non-Europeans, and specifically the use of fire, as wasteful and irrational.

In Belize, this negative view of slash and burn has driven many colonial and post-colonial interventions to modernize Maya farming practices.

Recent research, however, has shown that the lands of Indigenous Peoples around the world have reduced deforestation and degradation rates relative to non-protected areas. The southern Toledo district of Belize, where the majority of Maya communities are located, boasts a forest cover rate of 71 per cent, significantly higher than the national average of 63 per cent.

Further research has found that the species composition of contemporary Mesoamerican forests has been shaped by the agricultural practices of ancient Maya farmers.

In Belize, fire has been found to play a role in promoting ecosystem health and resilience and intermediate levels of forest disturbance caused by milpa can increase species diversity. Well-managed milpa farming can support soil fertility, result in long-term carbon sequestration and enriched woodland vegetation.

Research has also shown that previous studies of deforestation in southern Belize significantly overestimated the rate of deforestation due to milpa agriculture by not accounting for its rotational process.

Many researchers now believe that milpa is a more benign alternative, in terms of environmental effects, than most other permanent farming systems in the humid tropics. Indeed, findings such as these have led to a growing appreciation for the role of Indigenous Peoples in advancing nature-based and life-enhancing climate solutions.

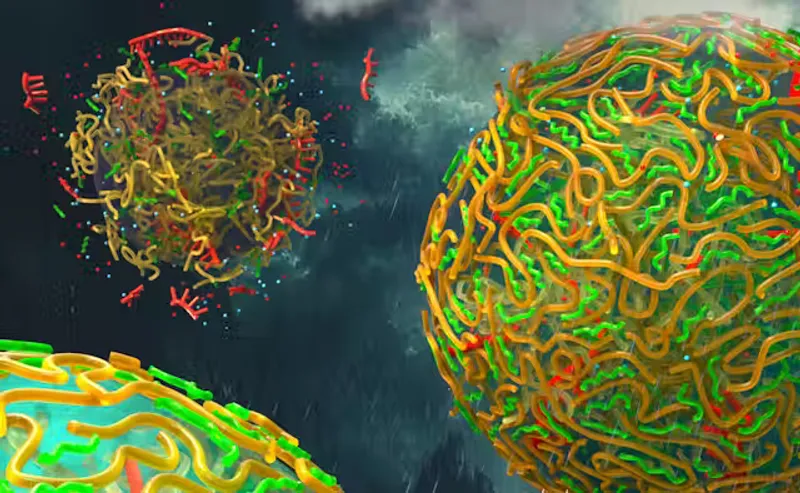

Unfortunately, research in the region has also found that climate change is undermining the ecological sustainability of milpa farming by forcing farmers to abandon traditional practices and adopt counterproductive measures in their struggle to adapt. In some cases, this has resulted in a decrease in the biodiversity and ecological resilience of the milpa system. This issue is compounded by the decreasing participation of young people, resulting in a further generational loss of traditional ecological knowledge.

Together, these issues are serving to alter and undermine a livelihood strategy that has proven sustainable for thousands of years. However, rather than call for Maya farmers to abandon slash and burn, we encourage support for the self-determined efforts of Maya communities to adapt to this changing climate.

Planting seeds of collaboration

Since winning a groundbreaking land rights claim in 2015, Maya communities in southern Belize have been working to promote an Indigenous future based on principles of reciprocity, solidarity, traditional knowledge, gender equity and, most significantly, se’ komonil, the Maya notion of togetherness and community.

Led by a collaboration of Maya leaders and non-governmental organizations, work toward this has included efforts to revitalize traditional institutions and governance systems, as well as the development of an Indigenous Forest Caring Strategy and fire-permitting system. In an effort to encourage and support the participation of youth in this process, Maya leaders have collaborated with the Young Lives Research Lab at York University to develop the Partnership for Youth and Planetary Wellbeing.

Building on previous research with Maya youth, the project has produced innovative youth-led research and education on the impacts of climate change, the importance of food sovereignty, traditional ecological knowledge and the struggle to secure Indigenous land rights in Maya communities. This work has been shared with global policymakers at the United Nations and local audiences in Belize.

Rather than fanning the flames of climate blame, we must work together to revitalize Indigenous knowledge systems and plant seeds of climate collaboration and care.![]()

James Stinson, Senior Research Associate and Evaluation Specialist, Young Lives Research Lab, Faculty of Education, York University, Canada and Lee Mcloughlin, PhD student, Global Sociocultural Studies, Florida International University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.