Stephen Bright, Edith Cowan University and Vince Polito, Macquarie University

Microdosing has become something of a wellness trend in recent years, gathering traction in Australia and overseas.

The practice involves taking a low dose of a psychedelic drug to enhance performance, or reduce stress and anxiety.

While the anecdotal accounts are compelling, significant questions remain around how microdosing works, and how much of the reported benefits are due to pharmacological effects, rather than participants’ beliefs and expectations.

We’ve just published a new study following on from two earlier studies on microdosing. Our body of research tells us some benefits of microdosing may be comparable to other wellness activities such as yoga.

Existing evidence

It’s not clear how many Australians microdose, but the proportion of Australian adults who have used psychedelics in their lifetime increased from 8% in 2001 to 10.9% in 2019.

After a slow start, Australian research on psychedelics is now progressing rapidly. One area of particular interest is the science of microdosing.

In an earlier study by one of us (Vince Polito), levels of depression and stress decreased after a six-week period of microdosing. Further, participants reported less “mind wandering”, which might suggest microdosing leads to improved cognitive performance.

However, this study also found an increase in neuroticism. People who score highly on this dimension of personality experience unpleasant emotions more frequently, and tend to be more susceptible to depression and anxiety. This was a puzzling finding and didn’t seem to fit with the rest of the results.

Microdosing vs yoga

In a recent study, Stephen Bright’s research team recruited 339 participants who had engaged in either microdosing, yoga, both or neither.

Yoga practitioners reported higher levels of stress and anxiety than those in the microdosing or control groups (participants who did neither yoga nor microdosing). Meanwhile, people who had practised microdosing reported higher levels of depression.

We can’t say for sure why we saw these results, although it’s possible people experiencing stress and anxiety were attracted to yoga, whereas people experiencing depression tended more towards microdosing. This was a cross-sectional study, so participants were observed in their chosen activity, rather than assigned to a particular group.

But importantly, the yoga group and the microdosing group recorded similarly higher overall psychological well-being scores compared with the control group.

And interestingly, people who engaged in both yoga and microdosing reported lower levels of depression, anxiety and stress. This suggests microdosing and yoga could have synergistic effects.

Our new research

Through a collaboration between Edith Cowan University, Macquarie University and the University of Göttingen in Germany, our most recent study aimed to extend these findings, and in particular try to get to the bottom of the possible effects of microdosing on neuroticism.

We recruited 76 experienced microdosers who completed a survey before undertaking a period of microdosing. Some 24 of these participants agreed to complete a follow-up survey four weeks later.

The results were published in the Journal of Psychedelic Studies this month. We found that like our earlier work, the 24 participants experienced personality changes after a period of microdosing. But the changes were not entirely what we anticipated.

This time, we found a decrease in neuroticism and an increase in conscientiousness (people who are highly conscientious tend to be diligent, for example). Interestingly, a greater amount of experience with microdosing was associated with lower levels of neuroticism among the 76 participants.

These results are more consistent with other research on the reported effects of microdosing and high-dose psychedelics.

So what does it all mean?

Our most recent findings suggest the positive effects of microdosing on psychological well-being could be due to a reduction in neuroticism. And the self-reported improvements in performance, which we’ve also observed in our past research, could be due to increased conscientiousness.

When considered together, the findings of our research suggest contemplative practices such as yoga might be particularly helpful for less experienced microdosers in managing negative side effects such as anxiety.

However, we cannot know for certain if the changes we’ve observed are due to microdosers holding positive expectations because of glowing anecdotal reports they’ve seen in the media. This represents a key limitation of our research.

As psychedelic drugs are illegal, it’s ethically complex to provide them to research participants — we generally have to observe them taking their own drugs. So another key challenge of this research is the fact we can’t know for sure precisely what drugs people are using, as they don’t always know themselves (especially for LSD).

Microdosing carries risks

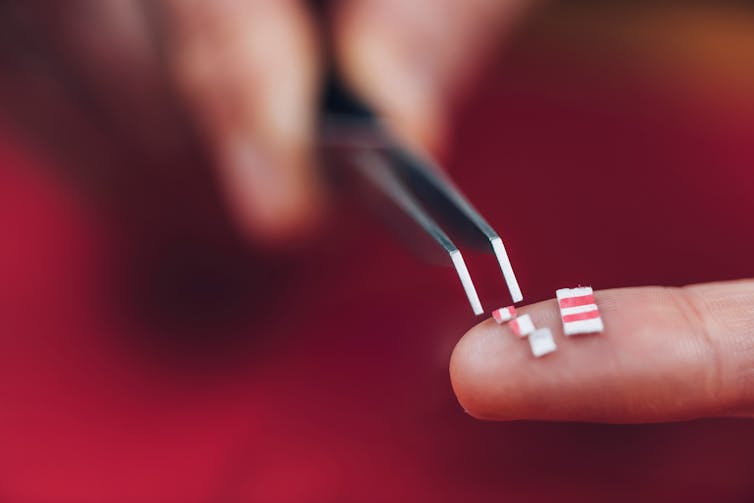

Given the illegal drug market is unregulated, there’s a danger people could inadvertently consume a potentially dangerous new psychoactive substance, such as 25-I-NBOMe, which has been passed off as LSD.

People also can’t be sure of the size of the dose they’re taking. This could lead to unwanted effects, such as “tripping balls” at work.

Potential harms like these can be mitigated by checking your drugs (you can buy at-home test kits) and always starting off with a much lower dose than you think you need when using a batch for the first time.

Where to from here?

Despite the hype around microdosing, the scientific results so far are mixed. We’ve found microdosers report significant benefits. But it’s unclear how much of this is driven by placebo effects and expectations.

For people who choose to microdose, also engaging in contemplative practices such as yoga might mitigate some of the unwanted effects and lead to better outcomes overall. Some people might find they get the same benefit from the contemplative practices alone, which is less risky than microdosing.

As a next step, one of us (Vince Polito) and colleagues are using neuroimaging to investigate the effect of microdosing on the brain.

If you practise microdosing, are based in Sydney, and are interested in taking part in this research, please email [email protected].![]()

Stephen Bright, Senior Lecturer of Addiction, Edith Cowan University and Vince Polito, Senior Research Fellow in Cognitive Science, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.